2.3 — OLS Linear Regression — Class Notes

Contents

Thursday, September 10, 2019

Overview

Today we start looking at associations between variables, which we will first attempt to quantify with measures like covariance and correlation. Then we turn to fitting a line to data via linear regression. We overview the basic regression model, the parameters and how they are derived, and see how to work with regressions in R with lm and the tidyverse package broom.

We consider an extended example about class sizes and test scores, which comes from a (Stata) dataset from an old textbook that I used to use, Stock and Watson, 2007. Download and follow along with the data from today’s example:Note this is a .dta Stata file. You will need to (install and) load the package haven to read_dta() Stata files into a dataframe.

Slides

Live Class Session on Zoom

The live class Zoom meeting link can be found on Blackboard (see LIVE ZOOM MEETINGS on the left navigation menu), starting at 11:30 AM.

If you are unable to join today’s live session, or if you want to review, you can find the recording stored on Blackboard via Panopto (see Class Recordings on the left navigation menu).

Problem Set

Problem Set 1 answers are posted on that page in various formats.

Problem set 2 (on classes 2.1-2.2) is due by 11:59 PM Sunday September 13 by upload on Blackboard.

Math Appendix: Covariance and Correlation

Variance

Recall the variance of a discrete random variable X, denoted var(X) or σ2, is the expected value (probability-weighted average) of the squared deviations of Xi from it’s mean (or expected value) ˉX or E(X).Note there will be a different in notation depending on whether we refer to a population (e.g. μX) or to a sample (e.g. ˉX). As the overwhelming majority of cases we will deal with samples, I will use sample notation for means).

σ2X=E(X−E(X))=n∑i=1(Xi−ˉX)2pi

Fpr continuous data (if all possible values of Xi are equally likely or we don’t know the probabilities), we can write variance as a simple average of squared deviations from the mean:

σ2X=1nn∑i=1(Xi−ˉX)2

Variance has some useful properties:

Property 1: The variance of a constant is 0

var(c)=0 iff P(X=c)=1

If a random variable takes the same value (e.g. 2) with probability 1.00, E(2)=2, so the average squared deviation from the mean is 0, because there are never any values other than 2.

Property 2: The variance is unchanged for a random variable plus/minus a constant

var(X±c)

Since the variance of a constant is 0.

Property 3: The variance of a scaled random variable is scaled by the square of the coefficient

var(aX)=a2var(X)

Property 4: The variance of a linear transformation of a random variable is scaled by the square of the coefficient

var(aX+b)=a2var(X)

Covariance

For two random variables, X and Y, we can measure their covariance (denoted cov(X,Y) or σX,Y)Again, to be technically correct, σX,Y refers to populations, sX,Y refers to samples, in line with population vs. sample variance and standard deviation. Recall also that sample estimates of variance and standard deviation divide by n−1, rather than n. In large sample sizes, this difference is negligible.

to quantify how they vary together. A good way to think about this is: when X is above its mean, would we expect Y to also be above its mean (and covary positively), or below its mean (and covary negatively). Remember, this is describing the joint probability distribution for two random variables.

σX,Y=E[(X−ˉX)(Y−ˉY)]

Again, in the case of equally probable values for both X and Y, covariance is sometimes written:

σX,Y=1Nn∑i=1(X−ˉX)(Y−ˉY)

Covariance also has a number of useful properties:

Property 1: The covariance of a random variable X and a constant c is 0

cov(X,c)=0

Property 2: The covariance of a random variable and itself is the variable’s variance

cov(X,X)=var(X)σX,X=σ2X

Property 3: The covariance of a two random variables X and Y each scaled by a constant a and b is the product of the covariance and the constants

cov(aX,bY)=a×b×cov(X,Y)

Property 4: If two random variables are independent, their covariance is 0

cov(X,Y)=0 iff X and Y are independent:E(XY)=E(X)×E(Y)

Correlation

Covariance, like variance, is often cumbersome, and the numerical value of the covariance of two random variables does not really mean much. It is often convenient to normalize the covariance to a decimal between −1 and 1. We do this by dividing by the product of the standard deviations of X and Y. This is known as the correlation coefficient between X and Y, denoted corr(X,Y) or ρX,Y (for populations) or rX,Y (for samples):

rX,Y=cov(X,Y)sd(X)sd(Y)=E[(X−ˉX)(Y−ˉY)]√E[X−ˉX]√E[Y−ˉY]=σX,YσXσY

Note this also means that covariance is the product of the standard deviation of X and Y and their correlation coefficient:

σX,Y=rX,YσXσYcov(X,Y)=corr(X,Y)×sd(X)×sd(Y)

Another way to reach the (sample) correlation coefficient is by finding the average joint Z-score of each pair of (Xi,Yi):

rX,Y=1nn∑i=1(Xi−ˉX)(Yi−ˉY))sXsYDefinition of sample correlation=1nn∑i=1(Xi−ˉXsX)(Yi−ˉYsY)Breaking into separate sums=1nn∑i=1(ZX)(ZY)Recognize each sum is the z-score for that r.v.

Correlation has some useful properties that should be familiar to you:

- Correlation is between −1 and 1

- A correlation of -1 is a downward sloping straight line

- A correlation of 1 is an upward sloping straight line

- A correlation of 0 implies no relationship

Calculating Correlation Example

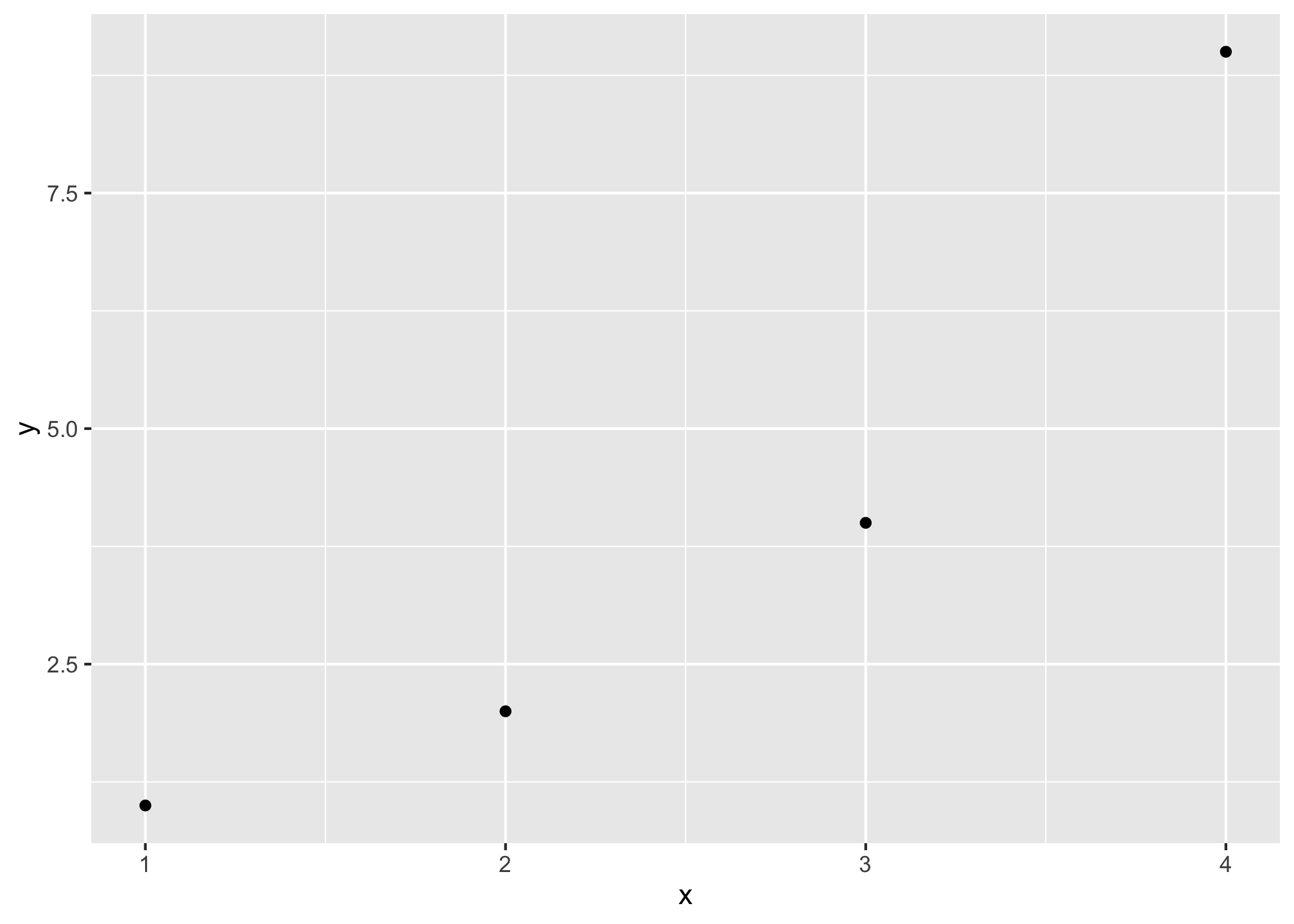

We can calculate the correlation of a simple data set (of 4 observations) using R to show how correlation is calculated. We will use the Z-score method. Begin with a simple set of data in (Xi,Yi) points:

(1,1),(2,2),(3,4),(4,9)

library(tidyverse)

corr_example<-tibble(x=c(1,2,3,4),

y=c(1,2,4,9))

ggplot(corr_example,aes(x=x,y=y))+geom_point()

corr_example %>%

summarize(mean_x = mean(x), #find mean of x, its 2.5

sd_x = sd(x), #find sd of x, its 1.291

mean_y = mean(y), #find mean of y, its 4

sd_y = sd(y)) #find sd of y, its 3.559## # A tibble: 1 x 4

## mean_x sd_x mean_y sd_y

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 2.5 1.29 4 3.56#take z score of x,y for each pair and multiply them

corr_example <- corr_example %>%

mutate(z_product = ((x-mean(x))/sd(x)) * ((y-mean(y))/sd(y)))

corr_example %>%

summarize(avg_z_product = sum(z_product)/(n()-1), # average z products over n-1

actual_corr = cor(x,y), #compare our answer to actual cor() command!

covariance = cov(x,y)) # just for kicks, what's the covariance? ## # A tibble: 1 x 3

## avg_z_product actual_corr covariance

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.943 0.943 4.33